- Images (46)

- Links (0)

- Agenda

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scratch Focus is an online streaming space that aims to encourage the exploration of Light Cone's catalogue, a constantly evolving collection that is now made up of around 5500 films. Each edition invites you to discover the work of a filmmaker from the collection on our website.

To mark the arrival of two new episodes of the General Picture series in our collection, as well as the digital restoration of a number of older episodes, we have conducted an interview with David Wharry about this project, which he began in 1978. Through the encounter with his body of work – which can be described as imaginary or potential cinema – the viewer is invited, in the words of Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki, to "act upon matter through sheer mental projection".1

· How did you begin your work as a filmmaker?

I arrived in France in 1972, when I was 22 years old. I had studied at art college in London, specializing in painting and I continued to paint for three or four years in Paris. I was working on a series of portraits and got the idea of making a dozen portraits of the same face with different expressions. A friend of mine had a 16mm camera and I thought, if I film this, I could create a superimposed, animated image of the face. I tried it, it was not very conclusive, but this was how I got hooked on filmmaking.

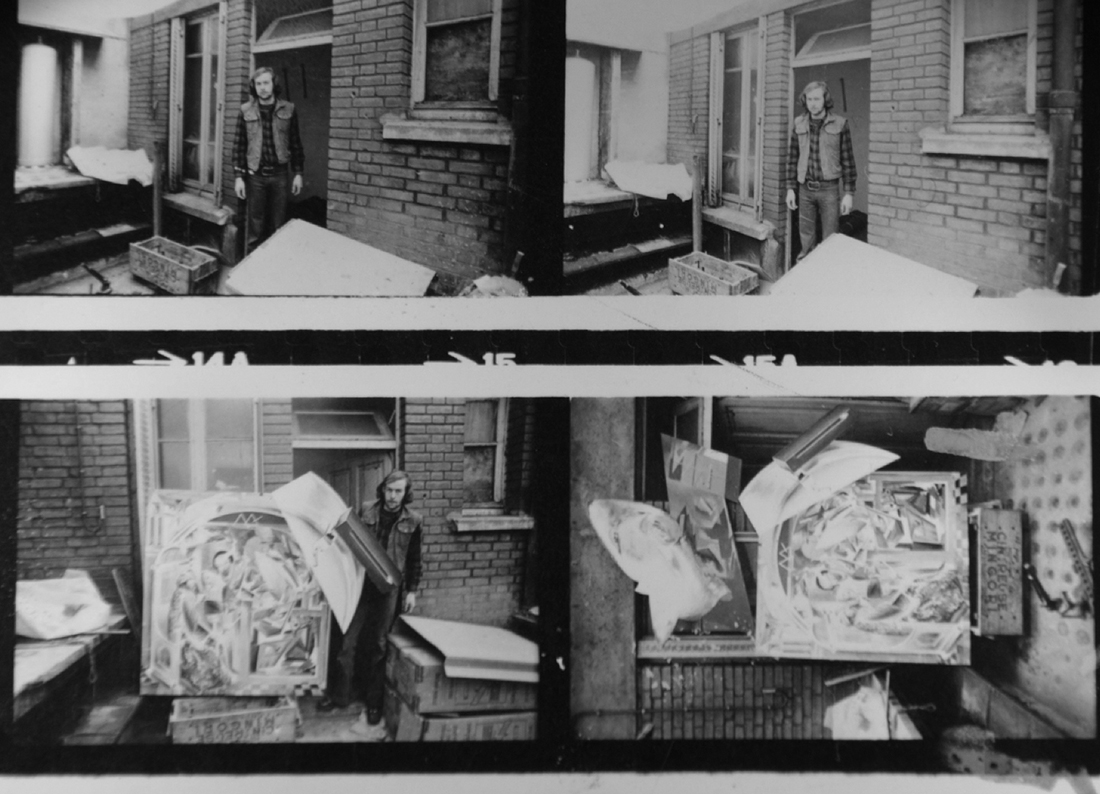

David Wharry with one of his paintings, rue du Château (Paris, 1973)

At the same time, there was an extraordinary series of screenings at the Cinémathèque, Une histoire du cinéma [A History of Cinema], whose curator Peter Kubelka showed absolutely everything that had been done in the realm of experimental and avant-garde film. I went to the Cinémathèque every day and I benefited from an extraordinary fast-track education. When we start making films, we have lots of ideas, and this gave me the advantage of seeing everything that had already been done…

And paradoxically, when I made my first film I felt that it was then that I was really beginning to paint for the first time. And the rest was… cinema!

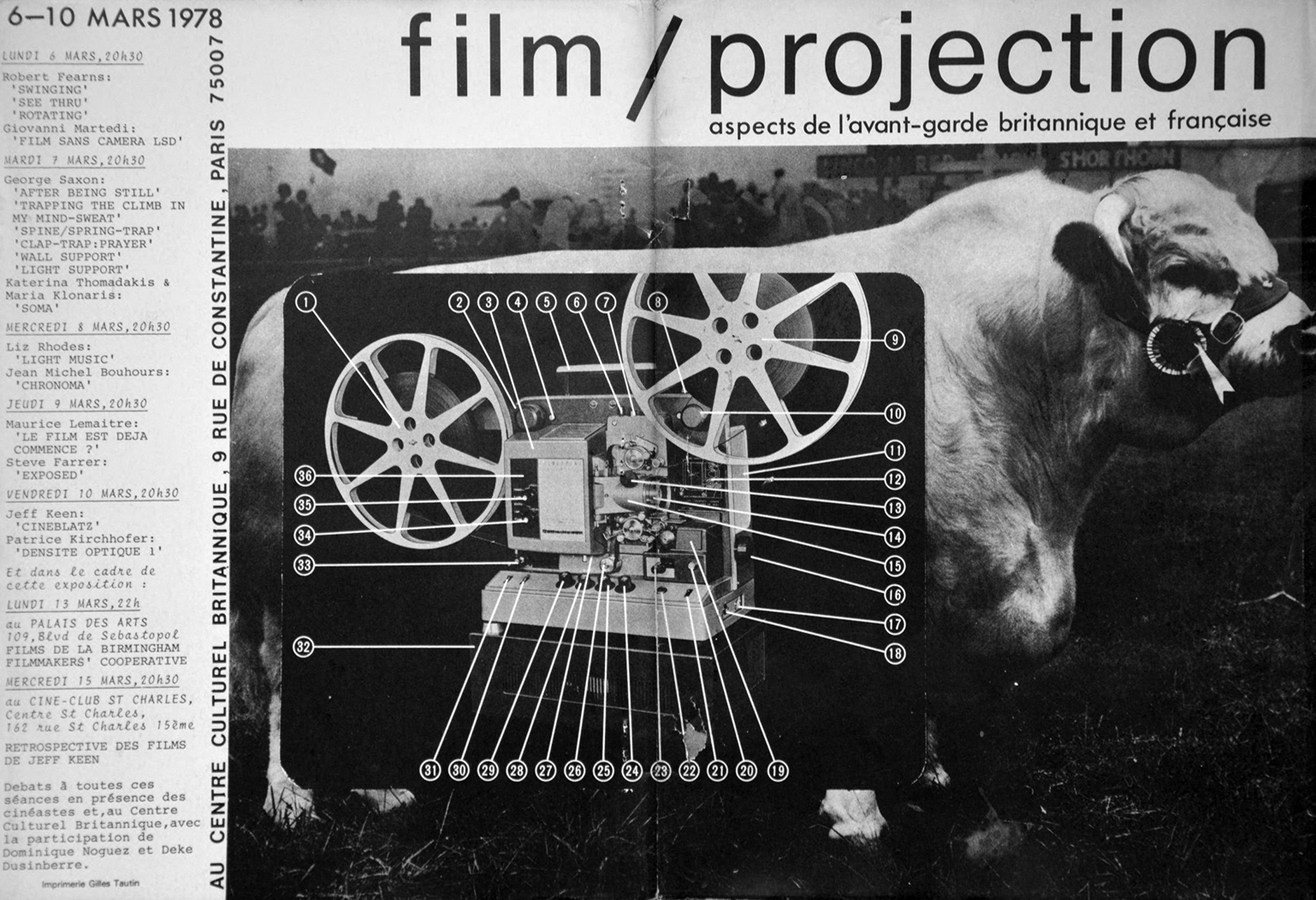

Film/Projection's programme, at the British Cultural Centre (Paris, 1978)

I made two films before General Picture: Horizontal Hold, of which I no longer have the original, and Dawn Patrol. During this time, I became a member of the Coopérative des Cinéastes [Filmmakers’ Cooperative], which was a kind of ancestor of Light Cone. Gisèle and Luc Meichler, Martine Rousset, Patrice Kirchhofer, Gérard Courant, among many others, were involved. It was a bit later that I began General Picture, toward 1978. At the time, I was working as projectionist at the British Cultural Centre in Paris. I did this for 15 years. At the beginning, with Deke Dusinberre, I organised two programs of expanded cinema there, the first of which was Film/Projection. We invited, among others, filmmakers from the London Filmmakers’ Coop such as Lis Rhodes, Jeff Keen, Steve Farrer and Ian Kerr.

· How did you conceive the idea for General Picture?

I think I can trace that back to my time at art school in London. I had realised to what an extent I had been indoctrinated, formatted. Painting had become a kind of restrictive intellectual process… Cinema suddenly took all that weight off me precisely because I didn’t know anything, I didn’t have any preconceived ideas. It was a complete liberation for me.

PHAETON

General Picture - Episode 5

1978 / 16mm / b&w / sound / 7'25

"Look at the image projected on the screen. Now, project the image onto the screen."

And when I began General Picture that was the idea: to be completely free, to not be limited by any style, to be able to work in different genres, to do whatever I wanted. I had a certain idea of the cinematic experience and I wanted to explore its different aspects, and that these explorations could all be part of one, ongoing work. I saw this as a series whose episodes could be shown separately, together, or in any order. I incorporated narrative links between the films from the very beginning. There are a number of things that reappear, a kind of narrative construction, especially in the first films.

A TOUCH OF VENUS

General Picture - Episode 9

1980 / 16mm / color / sound / 8'

"Let your senses make an image of the sequence."

I felt that there were many different things I could do, and I did them one by one. The notion, the idea of General Picture came to me from the very beginning. If, for instance, you want to write a novel, you don’t say to yourself, I’ll begin at the beginning and let the story write itself through to the end… In fact, it doesn’t happen like that. If you have a complete idea of the overall structure from the start, if you know exactly what the different parts will be, paradoxically, this gives you much more freedom. I believe very strongly in this idea of structure, of a framework – like a house in which there are many different rooms to explore.

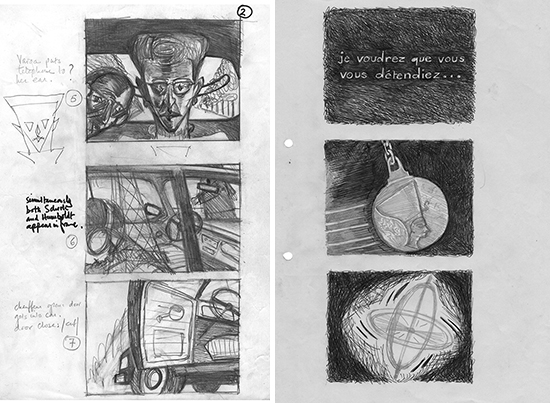

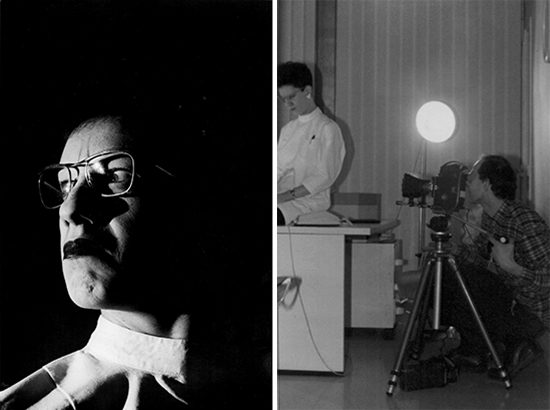

Storyboards and photos from the shoot of Carlton Dekker (1986)

· There is also a presence of cinephilia, for example, references to Feuillade…

Yes! For example, Suddenly Once More is directly inspired by Feuillade: it’s the beginning of Fantômas, where we see Fantômas in his various disguises. I was astounded when I saw it at the Cinémathèque. I also loved the idea of a serial film. So I began seeing General Picture also as a kind of serial.

SUDDENLY ONCE MORE

General Picture - Episode 6

1980 / 16mm / b&w / silent / 2'40

The multiple identities of Professeur Anatole Lacoste.

· How did you make El Cafetal?

I came across an old vinyl record in a junk shop, a Cuban record dating from the fifties. It was a zarzuela, a kind of cross between a musical and cabaret where each song is a separate scene. I wanted to make an invisible musical comedy – in Technicolor! So I started by photographing colours, but this didn’t work: the colours weren’t pure enough and all you could see was the film grain.

I thought about dyeing film. I tried this with pure, transparent acetate stock, but of course no dye would stick to it. A laboratory offered to process some black, negative film for me – so that the film would be completely clear but all the emulsion would stay on one side. I tried various clothing dyes, but again these colours didn’t work. In front of my house there was a Jewish baker who made enormous multistorey wedding cakes with incredible colours. He gave me a few plastic cups with the colourings he used, made from natural ingredients like turmeric and egg yolk.

I made solutions with these colourings in buckets and submerged the transparent film in them. I had a big workspace and I installed a system of pulleys across the ceiling. I would reel the film out of the bucket, wiping it with a paper towel and leave it suspended on the pulleys to dry. When I projected the film, there was absolutely no grain, nothing, just pure colour.

EL CAFETAL

General Picture - Episode 11

1981 / 16mm / color / sound / 38'

On a coffee plantation near Havana in the early 19th century, a slave’s impossible love for the owner’s daughter.

When it came to the editing, I listened to the songs with the help of a friend who translated the lyrics for me. I imagined it as a true musical comedy: shot – reverse shot, scene changes, etc. In fact, I had the idea that El Cafetal was a film that had once existed, an old Cuban film whose original had been lost and only the soundtrack had survived, and that I had to reconstruct this lost film. So you could say it was a kind of imaginary restoration project…

And when opened the film can three years ago to make a digital version, I was amazed how the colours hadn’t faded one bit in over 30 years.

· Could you talk about the change from the photochemical to the digital format in your work?

Before I put General Picture on hold for several years, there was of course already the possibility of working in video, in digital, but it didn’t interest me. Now I understand all the possibilities. The only difference is that with film, you have to calculate so much more precisely what you want to do beforehand, and have a good working knowledge of photography. Then you have to wait for the rushes to arrive… And when they’re not right, you have to redo everything again. With digital, you can change anything at will during the filming or editing, as many times as you want. Now I make my films on the kitchen table…

DREAM

General Picture - Episode 16

2020 / HDV / color / sound / 9'30

"I'm in a cinema watching the dream on the screen. The dream is a film."

The possibilities offered by the digital format are important for me… I had stopped making films and devoted myself to writing. But in fact I hadn’t really stopped because literature, fiction, is for me the ultimate form of cinema: as in General Picture, the reader makes his or her own film.

After a long pause, I returned to filmmaking with Point Blank, which is a kind of superimposition of those two ideas: reading and the cinematic experience. The idea again for Point Blank was to construct a film based on the soundtrack. I started by marking all the shot changes, that was my precise framework. I began by using different wallpaper patterns for each shot, then I switched to mandala-type images but none of this worked. Then one evening, watching a film on Netflix, I pressed the wrong button and activated audio description. I was amazed by the way scenes are described for visually impaired and blind people. This changed everything: I realized that what I had to do was “describe” each shot. And so I found myself writing again for a few months…

Today, all that I write is for films. At present I’m trying to write a western…

1 Klonaris/Thomadaki, "Technologies et imaginaires - art cinéma, art vidéo, art ordinateur", 1990

–––––––

Full list of General Picture episodes revised by David Wharry :

1. Freighters of Destiny (1980)

2. À Plate Couture (1979)

3. Wishful Thinking (1978)

4. For Eyes Only (1978)

5. Phaeton (1978)

6. Suddenly Once More (1980)

7. Entr'acte / Interlude (previously Prélude à la nuit) (1980)

8. European Crisis (1982)

9. A Touch of Venus (1980)

10. Body and Soul (1981)

11. El Cafetal (1981)

12. Written on the Wind (1983)

13. Carlton Dekker (1986)

14. Point Blank (2018)

15. The Screen (2020)

16. Dream (2020)

–––––––

Light Cone distributes David Wharry's films, you can watch them here.

We'd like to thank David for answering our questions.

Previous editions of Scratch Focus:

SEEKING PATTERNS: THE FILMS OF CAROLINE AVERY

CENTERS OF GRAVITY: TONY HILL'S WORK

FIVE FILMS BY LARRY GOTTHEIM

| address |

Light Cone 157 rue de Crimée 75019 Paris France |

|---|---|

| tel | +33 (0)1 46 59 01 53 |

| lightcone@lightcone.org |