- Images (38)

- Links (0)

- Agenda

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As part of the Scratch Focus series, where we highlight the work and the words of one of the many filmmakers in our collection, we are happy to share our recent interview with Pablo Marín. A native of Buenos Aires, he is a key figure in Argentine experimental cinema, as a filmmaker but also as a disseminator through research, critical writing, translation and programming. In his films, the lyrical is mixed with formal rigor in an attempt to explore the technical and material possibilities of Super 8. His latest film, Trampa de luz, is screening at numerous festivals this year and just won the Principal Online Prize at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival.

We invite you to view two of his previous short films here, which will be available on this page from July 30 to August 30, 2021.

· Your first films are part of a series called Sin Título (Untitled), a collection of explorations of the Super 8 camera beginning with Focus.

The Sin Título series, made up of seven films each the length of one cartridge, is a kind of autodidactic exercise. Each roll responds to a specific idea. Focus is the first film that I shot in Super 8 and in it I explore the frame-by-frame functionality. There is another film in the series in which I begin to investigate the idea of opening the camera and masking a part of the gate before rewinding – something I will return to later in other films. The idea was to explore the format and the camera as an instrument that can be opened and experimented with. They are small films that illustrate this exploratory process.

· How did you become interested in this format?

First of all, it had to do with the fact that I didn’t have a professional background in film: Super 8 was always a friendlier, more automatic format – anyone can grab a Super 8 camera and shoot. With 16mm everything is more complicated: you have to use a lightmeter and interpret how the image is going to look. The reason was also financial. I bought my first camera on an eBay-type website in Buenos Aires, and it cost me something like 2 euros. The choice of format was marked by the challenge to make a film with something like this.

On the other hand, there is also a historic aspect to it, since I was already in touch with Argentine experimental cinema, of which the most interesting period (starting in the 1970s) is a corpus of Super 8 films. This gave me the final push toward this format rather than others because I knew and understood it better.

· Why was Super 8 used so much in Argentina?

It has to do with financial reasons, but there are also many possible ramifications and explanations. The economic reason was the first one - the format’s inexpensiveness and the possibility it gave to escape the industry. Using Super 8 was a way to go through the backdoor, to avoid the cinematographico-industrial rationale. I think this was a great moment when cinema became much more democratic. Anyone could make a film. This was very encouraging. For that generation, it was a matter of taking a stand against the more industrial cinema by spending very little and beginning to explore what could be done with the format, its limitations, etc. I’m thinking above all of Claudio Caldini, whose formal and structural approach is very deep, as well as Jorge Honik and Laura Abel, and Narcisa Hirsch. There are many names but I would say that these are the figures whose works I still watch today, and many of the things they’ve done continue to fascinate me.

· In your films there is an interesting contrast between the things of your daily life, which you film in a lyrical and spontaneous way, and all the technical processes that you explore and control with the Super 8, such as multiple exposure.

I think it has a lot to do with being self-taught. It seems to me that the best way to explore a technology is to take it apart and see what’s inside: a certain curiosity which often results in breaking something and going beyond its limits. I see it as a dialogue between spontaneity, inspiration and a very concrete mastery of the technique. The creative process finds its boundaries in the material aspect: if I go further, the camera will break, or the image will not imprint… the boundaries of all these explorations had to do with something very concrete, material. I approach multiple exposure in the same way: wondering how many times can the same film strip receive light before it begins to affect what I filmed before. In this sense, there is always a big risk. When you film and rewind, editing in-camera, what you are filming at the moment is as important as what you filmed before and what you will film later. You have to have faith that it will all come out well.

This process of disassembling began with the Super 8 cartridges. In this sense, Argentine cinema of the 1970s has been a great inspiration. People of my generation knew what was possible thanks to what many of these filmmakers had already done. If Caldini, for example, was able to do some specific thing, I knew that it was possible. How it comes out is another question, because not everyone has Caldini’s talent. The material base allowed for these things. It’s also interesting to note the taboo of Super 8: in general, it cannot be rewound, it’s a format that goes only in one direction. You have to break it to be able to rewind it and load it again.

It’s not easy to explain this contrast between spontaneity and a more determined control. I think, for me it has to do with the fact that, since early on, I knew that the question of authorship or first-person filmmaking had to implicate cinema and its materials in a more protagonistic way. It was a way to take myself out of the frame, of not exposing myself so much. I couldn’t make films in the style of Brakhage or Mekas, who reveal themselves completely. I’ve always been interested in the relationship with structuralism: independently of content, the structure itself has to say something, be part of the content. My work is somewhere between things that happen to me or that I want to show and things that I know cinema can do by itself. It sounds nice to say it, but I often find this balance very difficult to achieve. I’ve felt and been told many times that my films don’t belong to any particular tradition and that they exist in some sort of no-man’s-land. This is difficult, too. In experimental cinema, categories help a lot to understand, to make films get shown, etc.

· Indeed, we identify these tendencies as separate from each other, but it doesn’t always have to be this way. A film of yours that illustrates this well is Denkbilder, whose title brings to mind Walter Benjamin’s “thought-images” and which takes the form of a travel journal filled with multiple exposures and fortuitous interactions between images.

I like to embrace this lack of definition. The concept of Denkbilder is one of an image from the past that is actualized in the present and, in turn, also includes a future. What struck me most about this term is that subjectivity and objectivity were intertwined and inseparable. You are looking at something that is an objective image and, at the same time, the product of a subjectivity. Multiple exposure seemed crucial to me to affirm this duality. One and the same frame contains forces that pull it in opposite directions.

DENKBILDER

2013 / Super 8mm / color / silent / 5'

« Fragments of a journey in which the geographical exploration merges with little emotional bursts, like the panels of a map folded into each other, impossible to separate. Berlin, Buenos Aires and the chaotic chances of building something close to a cartography of remembrances. »

This whole film comes out of my subjectivity, but the backdrop has to do with objective observations of Berlin, and then, thinking of Berlin and Walter Benjamin (since it’s the title of one of his texts), it becomes more blurred – the places are ones that Benjamin mentions or where he has been, like certain gardens and the Berlin zoo and the house of Goethe in Frankfurt, although there were a few things that didn’t come out due to some risky double exposure… then I began to retrace this path with fragments from my life and my own memories. I started to put into it things that would become my memories, everyday situations, etc. It seems to me that the film is an essay on this; it encapsulates everything and remains there, like a crystal, containing these two aspects. What also interests me in using multiple exposure or that kind of process is that these personal or autobiographical films, with such a concentrated rhythm and structure, contain months and months of filming compressed into five minutes. I am interested in this temporal game.

· There is a nice contrast between a film like Denkbilder and one like 1640, which has something more mechanical and abstract about it.

It’s a film made from medium-format slides (120). They are all photographs of the house where I lived in those years, the house where I was born in Buenos Aires. When the rolls were developed, I cut the slides to the width of 16mm and perforated them with a splicer. It’s a reduction from 6x6 to 16mm where I try to reconstruct something of a much bigger scale. It’s a vertical film where each frame shows a bit more of the original image – a materialist or structural approach in a certain sense, but which also transmits something very literal in autobiographical terms: to be able to pour into the projector a great number of images which are not even made with a camera.

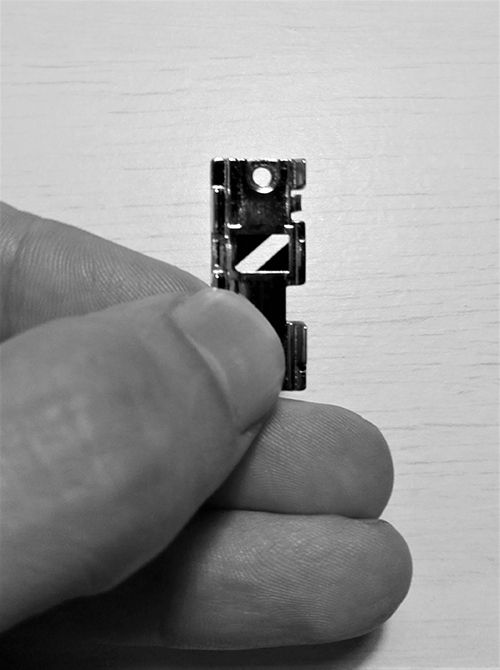

Manipulation of the Super 8 camera window (photo courtesy of Pablo Marín)

· Besides multiple exposure, another process that you explore consists in blocking a part of the frame in order to rewind and expose the hidden part later. Resistfilm is divided into four sections in which you explore various forms and possible combinations of this technique.

The discovery of this process had to do with controlling the multiple exposures. There is always the risk that, if you do something wrong, all that you’ve done before can crumble like a house of cards. The idea was to determine which parts were going to be exposed and which should be reserved to be exposed later or to protect things already filmed before. This is how the idea came about of doing multiple exposures and beginning to film parts that hadn't been exposed before, to arrive at a certain geometry or mirror play between parts of the image. Resistfilm is more of a study than a film in itself. I try various ways to cover up a part of the image, rewind, and then expose... all this came about from understanding Super 8 as a tool. As well as from the format of the cameras: one of the biggest weaknesses is that the cartridge acts not only as a cassette but also as the camera's pressure plate. Which means that it's the cartridge that presses the film against the gate, and as a result, the image fluctuates and is not very sharp. This weakness allows you to access the gate and play with it. I had seen many films where filmmakers attempted to do the same thing, but by covering the lens or putting mattes in front of it. For example, Asyl by Kurt Kren or what Tomonari [Nishikawa] does in the series Tokyo-Ebisu. This made me think that it always had to be a still shot with an unmoving camera, which I also like but I don't know if it would work with what I wanted to do in this film. One of the beautiful things about Super 8 is that you can move the camera with just a couple of fingers. I wanted to cover up a part of the frame but without losing mobility, zooming, etc.

RESISTFILM

2014 / Super 8mm / b&w / silent / 13'

« Super 8 film as Super film. In-camera investigations of (filmic) nature. Rustic homages to early avant-garde landmarks and wild landscapes of the 21st Century. »

The first thing I filmed for Resistfilm was the last section, the most complex one, but I didn't want to make a film that would begin with this degree of abstraction. Then I thought of a series of episodes through which the film would arrive there, something more gradual. The film begins with a whole shot of a forest, and then the frame is divided in two, then becomes more complex over the course of the segments. The title also responds to this: a kind of saturation of the frame and the mise-en-scène. Perhaps, the most narrative issue was precisely that: trying to shape it into a coherent journey, a logical journey of how this film constructs itself over time. It's impossible to show this film without being asked, “how did you do it?” I think that's part of the game. In any case, I like to think that the film is enjoyable in relation to the evolution of its form.

· How did Trampa de luz come about after a “research” film such as Resistfilm?

I think that Resistfilm is a study and at the same time something that exhausted itself in its making. Trampa de luz uses these processes in a completely different way, without drawing attention to itself. I think Trampa de luz is indebted to all those experiments which it integrates into something new, into a questioning that is much more spontaneous and less programmatic. I spent about two years working on it but filmed only three rolls.

Trampa de luz is also the first time I work with sound. I wanted a hint of sound without its being anything very defined, except for the melody made by the toy instrument. Besides this part, I liked the idea of a sound that never really stands on its feet. The first time that sound appears in the shot of the forest, people think it's a synchronous sound, while it's actually the sound of an optical head. There's something exciting about this materiality - when you go to see a film and hear that, you think: now the sound is going to start. I was interested in thinking of the film as a kind of antenna that was trying to capture something and that, at one point, catches this little music. It seems to me that the film has a wandering visual structure that goes on a kind of journey that doesn't really make any sense, and I wanted the sound to be an element that would amplify this strangeness.

· Angelus Novus also has a wandering structure and surprising elements in its edit.

I was interested in adapting things that I was reading, from a whimsical and, in a certain way, disappointing point of view. You shouldn't expect to see an adaptation of Angelus Novus by Walter Benjamin, because that's not going to happen. From Denkbilder onward, certain readings started to influence me more than film references or specific filmmaking processes. Both Angelus Novus and Trampa de luz are films where I feel the influence of poetry, of certain poetic structures and cadences, more than the cinematographic precision of structuralism or processes that I used in films like Focus.

–––––––

Light Cone distributes Pablo Marín's films, you can watch them here.

We'd like to thank Pablo for answering our questions.

Previous editions of Scratch Focus:

THOUGHTS ON COMMODITY LYRICISM: AN INTERVIEW WITH ZACHARY EPCAR

THE POTENTIAL CINEMA OF DAVID WHARRY

SEEKING PATTERNS: THE FILMS OF CAROLINE AVERY

CENTERS OF GRAVITY: TONY HILL'S WORK

FIVE FILMS BY LARRY GOTTHEIM

| address |

Light Cone 157 rue de Crimée 75019 Paris France |

|---|---|

| tel | +33 (0)1 46 59 01 53 |

| lightcone@lightcone.org |